Evolutionary Absorption: The Absolute in Pierre Teilhard de Chardin's "The Phenomenon of Man"

This is a review, by E.C. Quodlibet, of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin's "The Phenomenon of Man", with a special eye towards the question of the Absolute, what Teilhard calls "Omega".

Two Perspectives on the Absolute

Transcendence – is this not the essence of the Eternal? But no, Omega is, so to speak, halfway inside space-time and halfway outside. Transcendent and immanent, both. The non-dualist might say that the Absolute transcends the distinction of transcendence and immanence (here is a clear presentation of the issue of absorption). Alas, how are we ever to come to a conclusion on this issue, at which language grasps and fails? Are we not even more confused and entangled than when we began?

Transcendence – is this not the essence of the Eternal? But no, Omega is, so to speak, halfway inside space-time and halfway outside. Transcendent and immanent, both. The non-dualist might say that the Absolute transcends the distinction of transcendence and immanence (here is a clear presentation of the issue of absorption). Alas, how are we ever to come to a conclusion on this issue, at which language grasps and fails? Are we not even more confused and entangled than when we began?

Addendum: Notes on Love, Consciousness, Good and Evil

One approach would be to identify evil with what resists or rejects integration, that is, to identify it with isolation (of which Teilhard takes ‘racialism’ as a prime example), or at least with the pretension to isolation (here it would again be illusory). Systematization would then be good, and disintegration evil. This is indeed a commonplace occult scheme (see the above-mentioned Crowley on the so-called ‘black brothers’ who ‘shut themselves up in fortresses of love’). Are the deaths of the millions of organisms, even of higher animals, in the service of life, evil? Certainly not, for these deaths are part of life. But is there a death that cannot be put to this higher end, one that cannot be ‘hominised’ (to use Teilhard’s word)? This is precisely equivalent to Georges Bataille’s critique of the Hegelian systematic philosophy, that in it there is no death qua death, but only death qua life, in other words, death-in-life (and what of life-in-death?).

One approach would be to identify evil with what resists or rejects integration, that is, to identify it with isolation (of which Teilhard takes ‘racialism’ as a prime example), or at least with the pretension to isolation (here it would again be illusory). Systematization would then be good, and disintegration evil. This is indeed a commonplace occult scheme (see the above-mentioned Crowley on the so-called ‘black brothers’ who ‘shut themselves up in fortresses of love’). Are the deaths of the millions of organisms, even of higher animals, in the service of life, evil? Certainly not, for these deaths are part of life. But is there a death that cannot be put to this higher end, one that cannot be ‘hominised’ (to use Teilhard’s word)? This is precisely equivalent to Georges Bataille’s critique of the Hegelian systematic philosophy, that in it there is no death qua death, but only death qua life, in other words, death-in-life (and what of life-in-death?).

Or is there? Paradoxes have a way of taking their revenge on attempted solutions. In this case, what of the sentence “this sentence is false only”? Paraconsistent logic might respond that it is indeed only false… and also true! But does this capture the meaning of “only”? Is this an acceptable solution?

Or is there? Paradoxes have a way of taking their revenge on attempted solutions. In this case, what of the sentence “this sentence is false only”? Paraconsistent logic might respond that it is indeed only false… and also true! But does this capture the meaning of “only”? Is this an acceptable solution?

Two Perspectives on the Absolute

A great spiritual conflict is raging. Whether one takes it to correspond to a real difference of ineffable truths as they are variously experienced by competing traditions or resides in a merely interpretive issue (which itself would be perhaps to fall on one side of the debate), the conflict itself is clearly of great importance. The advocates of eternity tend towards an ineffability through and through, a more or less pure apophantic Absolute, while the partisans of duration decry such an ‘Absolute’ as an otherworldly nihilation of the quite effable facts of world and experience.

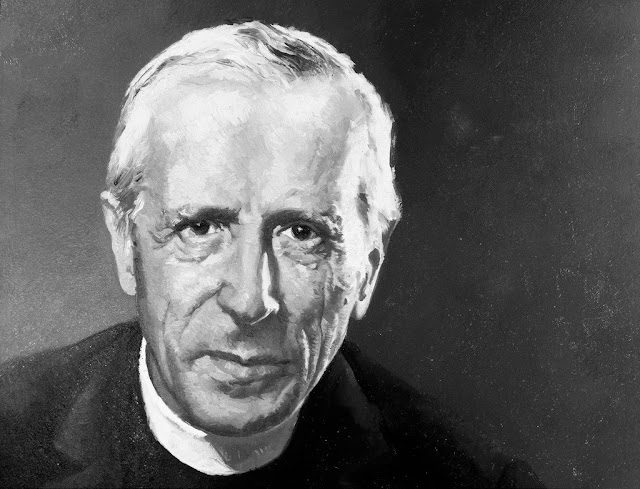

It is here that Pierre Teilhard de Chardin takes his stand, elaborated in such a visionary manner in The Phenomenon of Man. For this Jesuit, the first and most important development of the modern world is precisely the idea of development itself, or more particularly, the para- or meta-theory of evolution: “Is evolution a theory, a system or a hypothesis? It is much more: it is a general condition to which all theories, all hypotheses, all systems must bow and which they must satisfy henceforward if they are to be thinkable and true” (Teilhard, 219). Much could be said here of the influence not only of Darwin and other early evolutionists, but in a much more radical sense, of Bergson. And it is precisely at this point of duration-evolution that the radical historicity of Christianity becomes paramount, in opposition to a tendency that Teilhard denigrates as facile “pantheism”.

To clarify this essential and so far apparently insurmountable conflict, we can take Aldous Huxley’s The Perennial Philosophy as our foil. There, Huxley attacks Christianity, among other faiths, for its sickly focus on the merely historical, at the expense of the Eternal (which is further identified with Truth).

In Christianity, we might say that this historicity finds its culmination in the radically once-and-for-all fact of the Crucifixion, the philosophical implications of which Teilhard is wholly aware. Quite contrary to the non-dualist talk of the divine “ground” of existence so beloved by Huxely, Teilhard’s evolutionary Christianity can only truly be expressed in the terms of duration, of time, and of history, primarily in a series of critical points: the advent of the planet closing in on itself, the advent of life, the leap to thought, and primarily and most importantly, the advent of the Omega, spiraling towards us backwards through time, futural and yet at this very moment fully actual.

|

| Aldous Huxley, Western Advaitin |

The terrain of the battle is itself wholly spiritual. We can say that it is a matter of the status of materiality only insofar as this status is approached from the perspective of the Absolute itself. To be precise, the conflict between the two views we are here considering turns upon whether the Absolute is to be thought in terms of duration or in terms of eternity. Now, one might immediately determine that, to be really Absolute, it must be thought as both, or neither. And yet things cannot be that simple – can it really be that these two thinkers (and a score of others besides) do not see this? No, it is not so simple. The question inexorably becomes that of absorption, as it always does when the Absolute is at issue.

Absorption. The question of what holds absolute primacy over what, in fact over all the rest whatever it may be. But first we must dispense immediately with the facile reduction of non-dualism to the otherworldly, a reduction Huxley rejects. Non-dualism, the so-called perennial philosophy, has, in its Hindu form (as advaita vedanta), two apparently contradictory formulas, which date back to the Upanishads, and which must both be taken in conjunction to avoid establishing a higher-order dualism between Absolute and non-Absolute: first, tat tvam asi, “thou art that”; and second, neti neti, “not this, not this” (for “tat tvam asi”, see Chhāndogya Upanishad VI.viii.7; for “neti, neti”, see Brihadāranyaka Upanishad II.iii.6). The first expresses and integrative Absolute, or at least a universally absorbing one, while the second expresses a clasically apophatic negativity, where nothing in this world of illusion can possibly be the mystical ‘It’ that is the ultimate goal of all human activity. As noted, true non-dualism must maintain this paradox of both/and in all seriousness against the either/or of dualism (and I don’t mean for logical or linguistico-grammatical reasons).

For advaita, the Eternal absorbs the durational – there is no true or real temporal emergence of the Absolute; it is always realizable at any moment and by anyone. It is not that this world is rejected for love of another, more perfect world, but that this world is itself that perfect world (at every time and every place), and yet this remains unrealized by the mass of humanity, not in terms of mere logical assent or belief, but in terms of soul-based identification, of deeper realization than most even believe possible for experience. You are already enlightened, if only you would realize it and not persist in this illusion; the illusion itself is already the Absolute, if only you would realize it. It can always go another step, escape a logical determination, overflow the cracked vessels of conceptual-discursive thinking. And yet somehow it remains on the side of the Eternal, on the side of what its detractors call an “otherworld”. There are, as we shall see, quite a number of ways something can be “Absolute”, even “the Absolute”, quite a few methods of overflowing and, as we said before, of absorbing. And any given notion of this Absolute can absorb any other.

Where does good Teilhard stand on the nature of the Absolute, and how does his position differ markedly from that of the perennial philosophy? Is the Absolute of non-dualism properly Absolute according to the Jesuit priest? Certainly not, despite its claim of ‘including’ duration. But what indeed is ‘inclusion’? For Teilhard, this paradox between the plus and minus, between cataphatic and apophatic theology, is to be resolved in a different way, with a different medium of absorption, a different way of being Absolute. Here, as might be imagined, the Absolute falls ‘on the side of’ duration. But does it absorb the Eternal? To answer this question we must look more deeply into the attributes of Omega.

Teilhard identifies four such attributes: actuality (here the argument looks suspiciously like the Ontological Argument in a rather more compelling form); autonomy; irreversibility; and transcendence. The first two would be accepted without objection by the non-dualists, but the latter two are explicitly durational in character.

Irreversibility – the unique philosophical insight of Jankelevitch, as duration was of Bergson (arguably irreversibility functions in a broader mode than duration and absorbs it… but in light of the many problems we are investigating with regard to absorption, let us for now hold them distinct, as does Teilhard; at any rate it is a game of priority by mere implication). Irreversibility serves to tether all of time to a single point, Omega. This is the essence of the durational interpretation of the Absolute.

Transcendence – is this not the essence of the Eternal? But no, Omega is, so to speak, halfway inside space-time and halfway outside. Transcendent and immanent, both. The non-dualist might say that the Absolute transcends the distinction of transcendence and immanence (here is a clear presentation of the issue of absorption). Alas, how are we ever to come to a conclusion on this issue, at which language grasps and fails? Are we not even more confused and entangled than when we began?

Transcendence – is this not the essence of the Eternal? But no, Omega is, so to speak, halfway inside space-time and halfway outside. Transcendent and immanent, both. The non-dualist might say that the Absolute transcends the distinction of transcendence and immanence (here is a clear presentation of the issue of absorption). Alas, how are we ever to come to a conclusion on this issue, at which language grasps and fails? Are we not even more confused and entangled than when we began?

One method Teilhard brings to bear against the “pantheists” is a practical one. He critiques the nihilating quality of the non-dualist Absolute, since clearly one loses one’s ego, sense of isolate self, and so on, in the experience of non-dualism. For Teilhard this will not do, since the Omega Point must coincide with both (another absorption) the maximum individualization and the maximum integration:

The conclusion is inevitable that the concentration of a conscious universe would be unthinkable if it did not reassemble in itself all consciousnesses as well as all the conscious; each particular consciousness remaining conscious of itself at the end of the operation, and even (this must absolutely be understood) each particular consciousness becoming still more itself and thus more clearly distinct from others the closer it gets to them in Omega. (Teilhard, 261-2)

If absorption remained purely on the level of discourse (or conceptual thought), there might be no way to decide between them, so to speak. This is not to mention the fact that absorption can absorb other forms of absorption and so make the problem appear either insoluble or already solved. Teilhard’s critique here is that in actual fact, despite what might be absorbed by the non-dualist Absolute, it does not do what it claims to do; it does not say what it does and it does not do what it says. Absorb duration all you want, he seems to say, you are going to fail; perhaps proper to a partisan of religious tradition (if not strict orthodoxy), Teilhard forges an indestructible link between theory and practice. An improper understanding of the universe (that is, a non-evolutionary one) will lead one to an improper understanding of the Absolute, even, it would seem, in the sense of noesis (or gnosis, or whatever).

This claim may give us another way of approaching the problem, a clue. Perhaps the issue is not that between different views of the Absolute, but between different modes of access to said Absolute. Absorption is an infernal entanglement of paradoxes; indeed, maybe clarifying the nature of the Absolute discursively was a mistake from the start (but then again, perhaps firsthand exposure to the insolubility of the problem is itself indispensible for spiritual praxis). As we shall see, it is an issue of development, or better, of levels of development. How does one experience theoria in the mystical sense?

|

| A mystical sketch of the Crucifixion by St John of the Cross, striking for its radical perspective |

It might seem that to define the problem this way is to give immediate superiority to Teilhard’s account, since it falls, as we said, ‘on the side of’ duration, of development, even of levels of development (the series of critical points). Indeed, in the mystical traditions, the mode of access to the Absolute and the Absolute in itself are often impossible to really separate. Here, at the ultimate border of experience, the sublimest metaphysical truths coincide exactly with the most intimate inward perceptions, with the subtlest stirrings of the soul. And yet, perhaps we are being too hasty in suggesting Teilhard’s superiority on this issue.

It depends, one must conclude, on the level at which one’s soul exists, the degree of Being it has attained (however we define it). An apparently Teilhardian absorption, certainly. But what is our perspective in outlining this theory, what is our level? Certainly not that of theoria in the orthodox sense. It often occurs that in theorization about mysticism of whatever sort, the theorist assumes they have a bird’s eye view of the problem as a dispassionate ‘logical’ observer; but in mysticism this cannot possibly be the case (and who else would possibly have anything worthwhile at all to say about the Absolute but the mystic?). The theorist (either one who is not a mystic or at least who is not in theorizing functioning as a mystic, bowing, that is, to the strictures of logic, discourse, and human communication), quite contrary to academic pretension, is perhaps in some cases even less able to grasp the issue of the Absolute than the average person.

But holding this criticism aside, the point remains: from one level (the lowest?), duration holds sway. We cannot, however, ascribe this position to the ‘perspective’ of the Absolute, if such a thing as ‘perspective’ can be said to apply there in even an analogical sense. One can perhaps distinguish between the properly mystical Absolute and the merely philosophical one (not to say there are no mystic-philosophers; see Plotinus or Eckhart) by whether its existence relativizes all propositions or conceptual determinations or whether it founds a system of ‘knowledge’, ‘philosophy’, and so on. Teilhard, of course, bows to his religious orthodoxy and admits that the transcendence of Omega cannot be grasped by the human intellect (see the footnote on 298). And yet for him the transition from the ineffable to the effable is not so insurmountable as the perennial philosophy holds it to be; this is at least his claim as a scientist, one he is surely entitled to make whether we agree with him or not.

So we have seen that the durational absorption in terms of access to the Absolute (and remember, this access for Teilhard is a process of involution and cosmogenesis; quite a practical difference with his opponents), under the guise of levels of development, does not decide the issue. Is there some other way to do so? Is there such a thing as an Absolute Absorption? Since absorption is a discursive, conceptual, or whatever other kind of phenomenon, this issue does not admit of an easy answer, the relation between language and experience being fraught in general, and in the case of the Absolute being positively maddening. This question must be left aside; such an achievement would be akin to the advent of the Omega Point, or the manufacture of the Philosopher’s Stone in another vocabulary.

Addendum: Notes on Love, Consciousness, Good and Evil

Love. In Teilhard’s system, love has a privileged function, being the linchpin of his own unique version of the so-called Ontological Argument for God’s existence. The Omega attracts us, he says, it is a real tendency, expressed and evidenced on every level of existence and throughout all of cosmic history. We cannot truly love what is not real, and therefore, he concludes, the Omega is actual just as much as it is futural. And yet it nevertheless remains for it to work its magic and end the world (at least, as we know it). It would perhaps be worthwhile to compare and contrast Teilhard’s views on love as a cosmic, metaphysical principle or force with those of Aleister Crowley.

|

| A 3rd century painting of an "Agape Feast", or "Love Feast", connected to the receiving of the Eucharist |

Consciousness. Consciousness can only progress. It can never go backward. In going backward, it would merely be elongating itself, taking into account more elements, and therefore in actuality really going forward. One is reminded of a common problem in meditation, namely that of thinking, and then thinking that one is thinking, and constantly absorbing things at higher and higher removes. Reflecting on reflecting, and so on, as in the system of Fichte. The necessity of progress would seem to be guaranteed by the irreversibility of duration. And yet it may all come crashing down, Teilhard suggests. There really is no contradiction, if only for the presence of faith in Omega.

Good and Evil. Teilhard sees extraordinarily clearly the necessity of evil in his system: “True, evil has not hitherto been mentioned, at least explicitly. But on the other hand surely it inevitably seeps out through every nook and cranny, through every joint and sinew of the system in which I have taken my stand” (311). Integration includes that of evil. What would be Absolute and yet not contain evil, which is so obvious in front of our very eyes? There are in general two ways of approaching evil in theological terms: first, denying its reality (evil is what is unreal or illusory); second, systematically reinterpreting evil as in fact good. The first is taken by, say, Gnosticism. The second is taken by numerous orthodox religions. Teilhard’s position on the issue is more nuanced than either of these traditional interpretations.

One approach would be to identify evil with what resists or rejects integration, that is, to identify it with isolation (of which Teilhard takes ‘racialism’ as a prime example), or at least with the pretension to isolation (here it would again be illusory). Systematization would then be good, and disintegration evil. This is indeed a commonplace occult scheme (see the above-mentioned Crowley on the so-called ‘black brothers’ who ‘shut themselves up in fortresses of love’). Are the deaths of the millions of organisms, even of higher animals, in the service of life, evil? Certainly not, for these deaths are part of life. But is there a death that cannot be put to this higher end, one that cannot be ‘hominised’ (to use Teilhard’s word)? This is precisely equivalent to Georges Bataille’s critique of the Hegelian systematic philosophy, that in it there is no death qua death, but only death qua life, in other words, death-in-life (and what of life-in-death?).

One approach would be to identify evil with what resists or rejects integration, that is, to identify it with isolation (of which Teilhard takes ‘racialism’ as a prime example), or at least with the pretension to isolation (here it would again be illusory). Systematization would then be good, and disintegration evil. This is indeed a commonplace occult scheme (see the above-mentioned Crowley on the so-called ‘black brothers’ who ‘shut themselves up in fortresses of love’). Are the deaths of the millions of organisms, even of higher animals, in the service of life, evil? Certainly not, for these deaths are part of life. But is there a death that cannot be put to this higher end, one that cannot be ‘hominised’ (to use Teilhard’s word)? This is precisely equivalent to Georges Bataille’s critique of the Hegelian systematic philosophy, that in it there is no death qua death, but only death qua life, in other words, death-in-life (and what of life-in-death?).

Since it is overwhelmingly schematized with regard to duration (in fact with regard to the Omega Point), the system takes priority over the particular. And yet Teilhard wants to insist on the maximum individualization of both Omega and its parts. This leaves us in a difficult position with regard to determining the nature of evil in any given case. Who is to say whether any particular and apparent ‘isolation’ is not in fact a greater integration? Indeed, is evil even possible? Can systematization be resisted?

This state of affairs calls for an analogy. In formal logic, the “liar paradox” refers to the paradox of evaluating the statement “this sentence is false”. If the statement is true, it is false (since that is what it says), but if it is false then it must be true (since that is the negation of what it says). While this is a huge problem for classical logic, there are numerous approaches to evaluating the statement in other logics. In paraconsistent logic, statements can be both true and false. So the liar sentence would be true… and also false. No more paradox.

Or is there? Paradoxes have a way of taking their revenge on attempted solutions. In this case, what of the sentence “this sentence is false only”? Paraconsistent logic might respond that it is indeed only false… and also true! But does this capture the meaning of “only”? Is this an acceptable solution?

Or is there? Paradoxes have a way of taking their revenge on attempted solutions. In this case, what of the sentence “this sentence is false only”? Paraconsistent logic might respond that it is indeed only false… and also true! But does this capture the meaning of “only”? Is this an acceptable solution?

The analogy to the case of absorption/systematization is interesting. Can something be essentially “isolated”? What if “isolation” is part of the system (e.g., what if the system absorbs isolation as merely the particular individualization that accompanies that of Omega?)? Can something be “isolated only, not part of the system”? Or can the system merely absorb that apparent difference within its higher-order systematicity? The answer to this question, which is far from clear, determines whether true evil is possible in a system such as Teilhard’s. It also determines whether, in a more general sense, the Absolute can be logically thought at all, in even a rudimentary sense. If it were not for the evidence of millenia of mystical insight, we would be totally in the dark. But does this not itself fall on the side of the Eternal? Now it is clear that with regard to the problem, we must either think much more or much less.

Comments

Post a Comment